Tunnel vision?

Following the overwhelming response to his dismissal of video games as a potentially artistic medium, Roger Ebert

returned to the subject in a recent blog post. After looking into the matter further, his new conclusion is that he was right the first time: video games are not art, and furthermore never will be during the lifetime of anyone currently alive.

The response from the gaming community has been pretty vocal, albeit

not as universally outraged as last time.

Ebert's latest post is written with the same flippant disregard that has characterized all of his public opinions on video games. His responses to

Kellee Sanitago's TED talk are superficial and demonstrate that he has done little-to-no further research beyond watching the online video of said discussion. Besides reiterating his original opinion in the comparative context of cave paintings (which he prefers to video games), he mostly argues the subjective semantics of the term "art." He's open about his bias towards film, but then doesn't give video games a fair chance in light of this, instead referring to the financial structure behind the industry as reason enough to discount it as a potential site of artistic work. As though cinema is not significantly dictated by business models and economics.

In discussing Santiago's examples of artistic games Ebert makes it exceedingly clear that he has not played them. His questions about

Flower in particular ("Is the game scored? ... Do you control the flower?") demonstrate a complete lack of familiarity with the game. He hasn't bothered to educate himself in a practical sense and so of course his opinion hasn't changed. In order to understand games one has to play them, as the experience of engaging with the interface is equally important to understanding of the work behind the project or the meaning conveyed therein. Judging a game without playing it would be like saying you've seen a movie after looking at a series of still frames.

In Flower you control, you guessed it, a flower petal blowing in

the wind and try to spread beauty to your surrounding environment

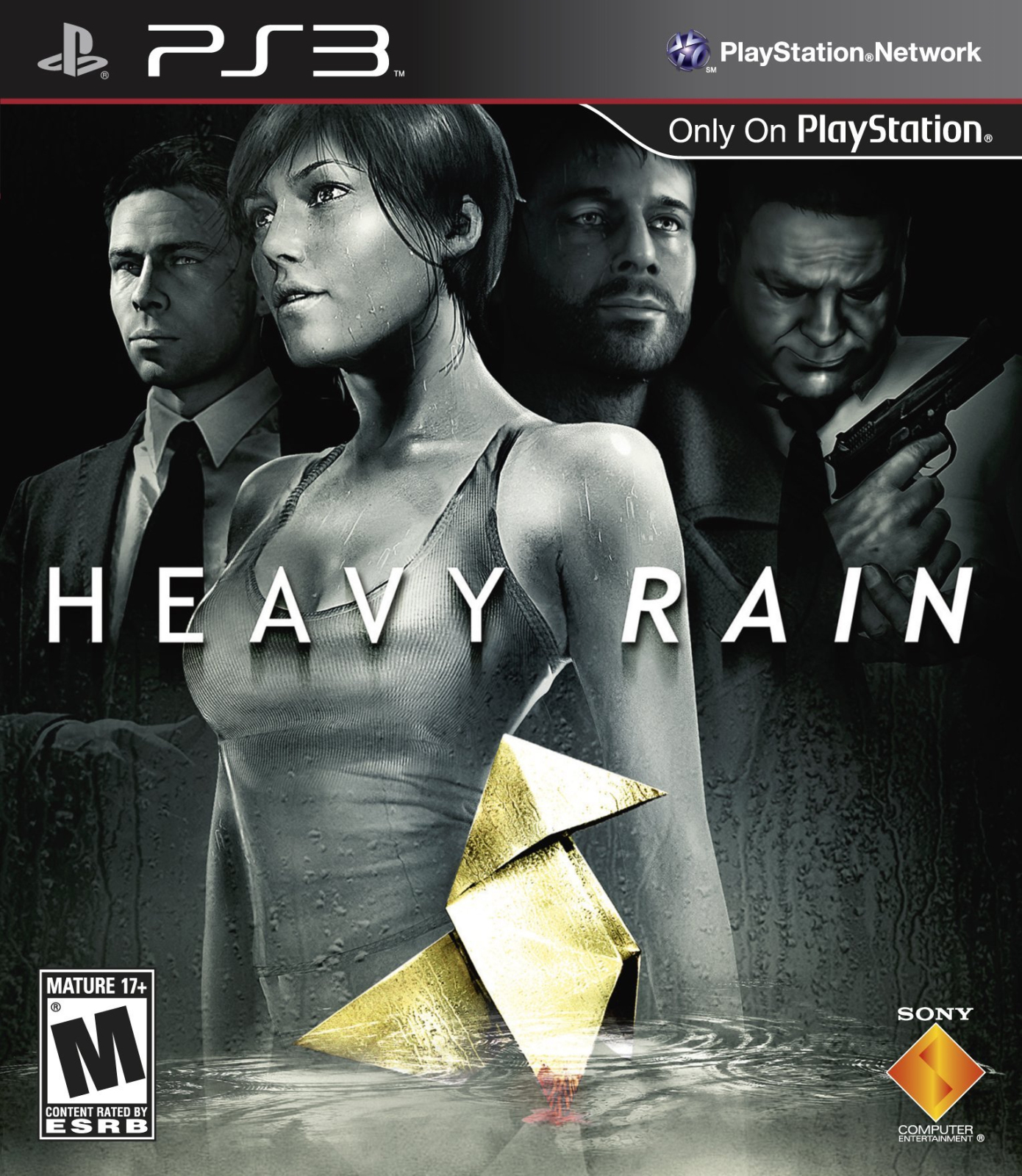

That's actually a point I was planning to make in the context of

Heavy Rain. Having played through the entire game and now gotten some distance from it, I want to return to

my earlier points about

what the game accomplishes.

I spoke a lot about causality and the freedom that

Heavy Rain gives the player to make choices and explore their consequences. Having played through the entire game I can now say that the degree to which the game allows you to make decisions with branching narrative impacts is somewhat less than I initially believed. There are certainly an incredible number of choices to make and different endings to the story they can result in, but some of the most important ones are more clearly indicated and binary than I expected. The story is also severely flawed in ways that have been

well-documented online.

Despite all of these criticisms, however, I still contend that

Heavy Rain represents a significant artistic achievement in gaming. It has many problems, granted, and in a lot of ways it fails to transcend being an obviously rule-based, linear narrative video game. But all of this is easy to say after-the-fact and says nothing of the actual gaming experience. It is in the engagement with

Heavy Rain that the game achieves something that I would call art.

In Heavy Rain there are choices and consequences,

but none of them are wrong in the traditional sense

Regardless of the flawed narrative or frustrating control scheme,

Heavy Rain draws you into the experience in a way that few games can. It is incredibly immersive because while you're playing you really do believe that your actions have serious narrative consequences. You feel the weight of every decision in a simultaneously realistic and dramatic sense, and so every choice is compelling. It's easy to criticize the game once you've explored every option and witnessed firsthand its limitations, but in the act of playing the game it makes you feel and consider your options even as you control your actions. That's only one approach to the question of creating art with a video game, but it is a far cry from the winning or losing binary that Ebert describes.

My point is that the actual playing of games is an integral aspect of the medium, and so any question as to their quality, content, or artistic achievement cannot ignore this facet of the experience. If an interactive medium can force you to question and consider our real world existence in any form then is that not art? Again the debate boils down to subjective semantics, but to me art is that which colours human life by appealing to our senses, thoughts, and emotions. It works upon us through the cognitive faculties that give us our very being. I think Mr. Ebert is wrong in saying that video games cannot achieve this.

I have played games that have affected me, made me pause and reconsider my beliefs.

Braid forced me to question my memories and thus myself, while playing

Bioshock drove me to think about human nature. Through

Heavy Rain I explored the nature of causality and the power of choice. These are meagre artistic accomplishments for what is admittedly an infantile medium, but they are important ones nonetheless. They show that there is potential for great things in interactive entertainment, just as there is potential in all forms of the arts.

The lovely and poignant Braid forces us to question our memories and actions

by using the flow of time as both a plot point and a game mechanic

That the majority of productions are schlock and the industry is dictated by financial gain is simply not enough reason to discredit what good there is or what good there could be. Video games deserve a chance for recognition and in order for that to happen they have to be considered on their own terms. They need to be given the benefit of the doubt, and above all else they need to be played

The debate as to whether or not games can be art goes on, and likely will continue to for a long time to come. I have made it clear where I stand, and will continue to do so with my Games As Art posts. Now, the debate about whether or not

art can be games? That's a whole other story...